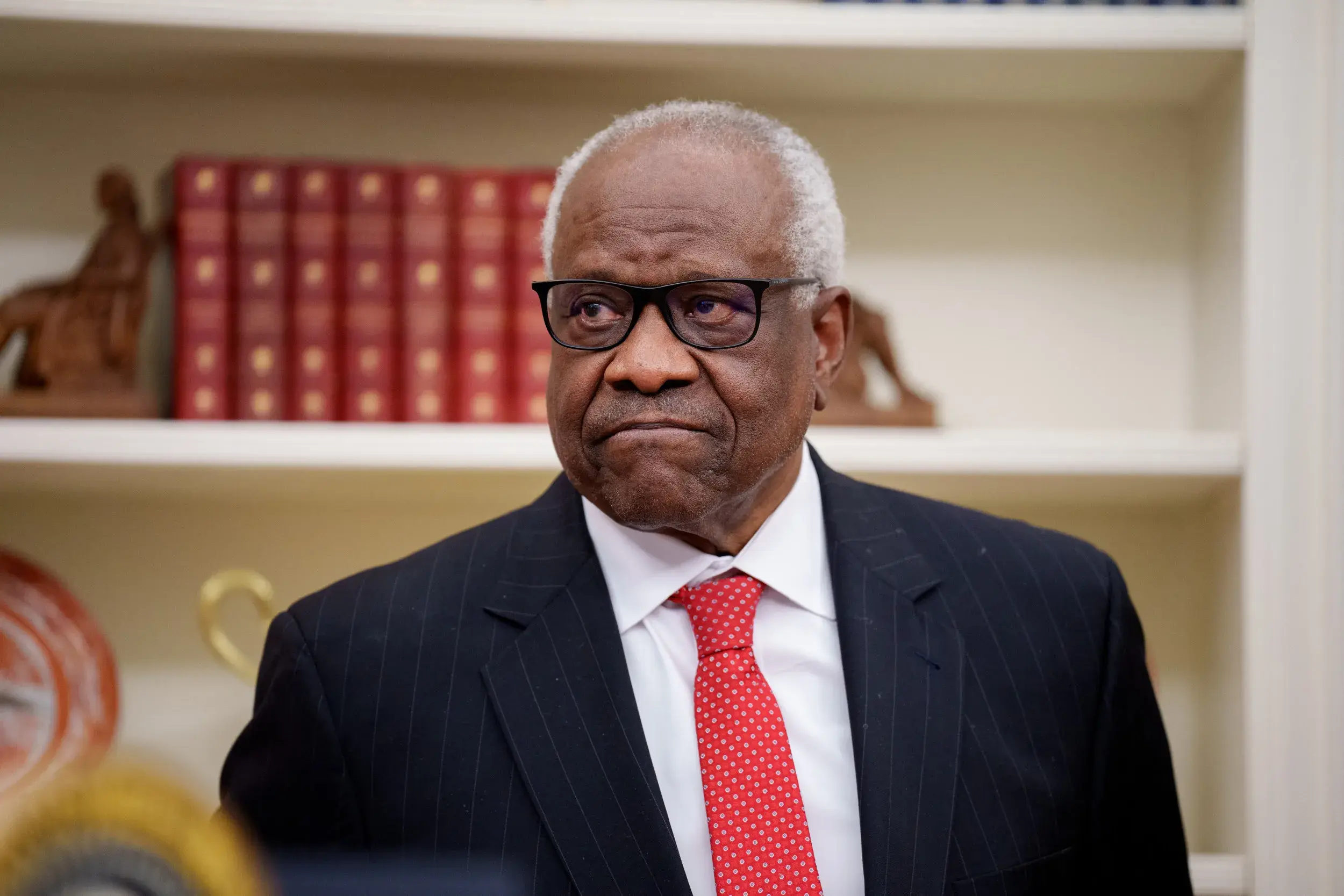

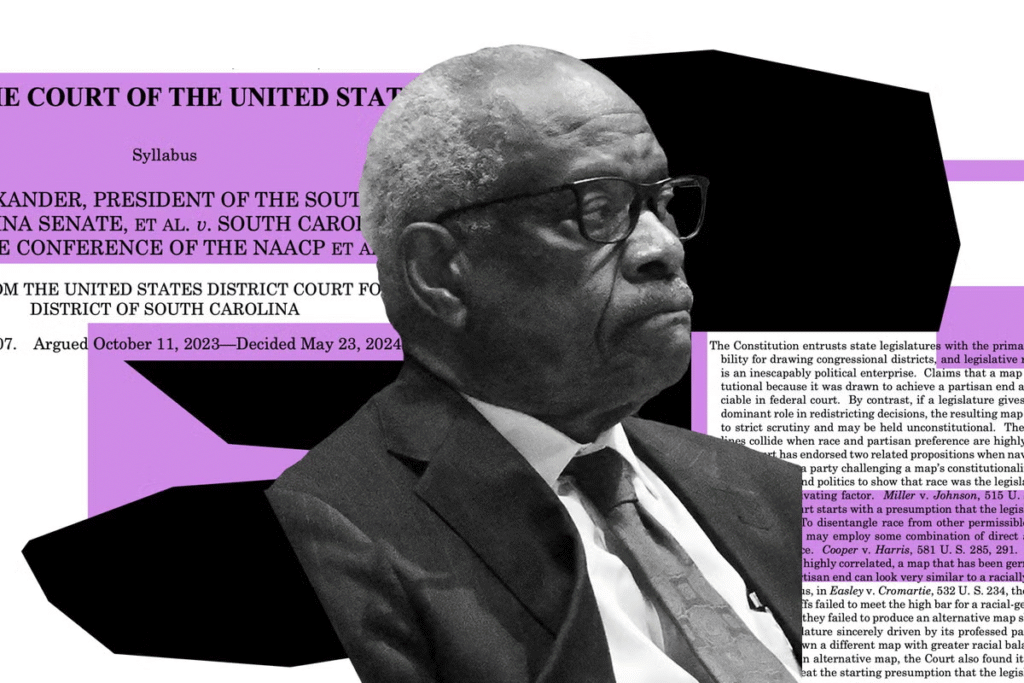

Clarence Thomas Challenges Race Based Districting While Marking Thirty Four Years On Supreme Court

Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas has once again ignited debate across the political spectrum, using a recent Supreme Court hearing to question the legality and morality of race-based redistricting under the Voting Rights Act.

His sharp questioning during oral arguments this week underscored the conservative bloc’s growing skepticism toward racial considerations in drawing congressional districts and reaffirmed Thomas’s long-standing belief that the Constitution demands colorblind governance.

The case before the Court involved Louisiana’s ongoing dispute over its congressional map, which was redrawn under federal court orders to create an additional majority-Black district.Civil rights advocates have argued that such districts are necessary to ensure fair representation of minority voters, while opponents contend that the process violates the Equal Protection Clause by making race the defining factor in electoral boundaries.

Thomas, now the longest-serving member of the Supreme Court and marking thirty-four years on the bench this week, pressed Louisiana Solicitor General Benjamin Aguinaga on the paradox of being compelled to use race as a guiding criterion in district design.His line of questioning cut directly to the philosophical and constitutional heart of the issue.

“Would the maps that Louisiana have currently be used if they were not forced to consider race?” Thomas asked pointedly. Aguinaga’s response was candid: “We drew it because the courts told us to. They said a majority-Black district was required. And our legislature saw the marching order.”The exchange highlighted the inherent tension in federal voting rights law as it has evolved over the decades — a tension between the desire to correct historic racial discrimination and the constitutional imperative to treat citizens as individuals rather than members of racial groups.

Thomas’s skepticism reflected his view, deeply rooted in decades of jurisprudence, that attempts to remedy inequality through race-conscious policy often entrench the very divisions they aim to eliminate.Observers in the courtroom described Thomas’s tone as both firm and reflective. He appeared unconvinced that creating districts based primarily on racial composition could ever be reconciled with the ideal of equal protection under the law.

“If the entire basis of the district is race, how can it ever be anything other than discriminatory?” one legal scholar paraphrased his concern afterward.For Thomas, the act of drawing lines according to skin color, no matter the intention, distorts the democratic process by substituting racial arithmetic for individual choice.

The hearing comes at a moment of both legal and personal significance for the justice.Thirty-four years have passed since his narrow Senate confirmation in 1991 — a 52–48 vote that followed one of the most contentious confirmation battles in American history.

For Thomas, who has endured decades of political attacks and media scrutiny, the anniversary serves as a testament to endurance and principle.His critics have called him rigid, while his admirers hail him as the intellectual anchor of constitutional originalism on the Court.Mark Paoletta, a longtime friend and former official in the Trump administration, commemorated the milestone with words of gratitude and admiration.

“Thirty-four years ago today, Justice Clarence Thomas was confirmed 52–48,” Paoletta wrote in a statement.“It’s impossible to overstate how important Justice Thomas’s confirmation has been to the saving of our constitutional Republic.”He went on to describe the justice’s influence as transformative, crediting him with helping to shape the Court’s most significant rulings in a generation.

Those rulings include a list of decisions that have defined modern constitutional interpretation: Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which overturned Roe v. Wade; Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard, which dismantled race-based affirmative action; New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen, which expanded gun rights; and several administrative law cases that curbed the power of federal agencies. In each, Thomas’s writings — whether in majority opinions or concurrences — have pushed the Court toward a stricter reading of the Constitution’s text and original meaning.

Paoletta emphasized that the seeds of today’s conservative Court were planted the day Thomas took his oath.“The beginning of today’s Court started when Justice Thomas was confirmed thirty-four years ago,” he said.“After the Democrats launched an all-out war, complete with lies and smears, to not only defeat him but to destroy him — they failed spectacularly.

”Indeed, Thomas’s confirmation hearings remain one of the most bitter episodes in the history of judicial nominations.Facing allegations of misconduct that he vehemently denied, Thomas memorably described the proceedings as a “high-tech lynching for uppity Blacks who in any way deign to think for themselves.

”His defiant speech before the Senate Judiciary Committee marked a defining moment in American political culture and cemented his image as both a survivor and a steadfast conservative.Three decades later, Thomas’s critics have continued to target him, raising questions about his financial disclosures, his friendships, and his political leanings.Yet the justice has consistently brushed aside such controversies, choosing to focus instead on his judicial philosophy and the work of the Court.

His defenders argue that the persistence of these attacks reflects the left’s frustration with his intellectual influence rather than any legitimate ethical concern.“Democrats have continued to attack him with despicable lies and smears,” Paoletta said. “And they have continued to fail in spectacular fashion.”Thomas’s jurisprudence, while often controversial, has proven remarkably consistent.From his earliest days on the bench, he has championed the idea that the Constitution must be read as it was understood by those who wrote and ratified it.

He has rejected modern theories that interpret the document as a living text subject to shifting social standards.For Thomas, fidelity to the Constitution’s original meaning is the ultimate safeguard against tyranny.

That belief has guided his approach to issues ranging from affirmative action to administrative power.In Harvard, Thomas wrote that “eliminating racial discrimination means eliminating all of it.”In Dobbs, he questioned not only abortion rights but also the broader doctrine of “substantive due process,” arguing that courts have used it to invent rights not grounded in the Constitution.

And in cases like Loper Bright and Lucia, he has sought to roll back decades of judicial deference to federal agencies, restoring authority to the legislative and judicial branches.Supporters see these decisions as victories for liberty and accountability; detractors view them as reactionary and destabilizing.

Yet even critics concede that Thomas’s influence on American law has been profound.His reasoning often serves as the blueprint for future majorities, and his opinions are studied by scholars and judges alike for their depth and clarity.

As he engaged with Louisiana’s solicitor general this week, Thomas appeared to channel the same intellectual independence that has defined his career.His questions were not just about the specifics of the state’s redistricting map but about the philosophical premise behind it.Should the government have the authority — or the obligation — to sort citizens into racial categories for political purposes? For Thomas, the answer has long been no.

Legal analysts believe the case could serve as a pivotal test of how far the current Court is willing to go in dismantling race-based policies.While Chief Justice John Roberts has previously cautioned against race-conscious remedies, Thomas’s view goes further: that any use of race by the government is inherently unconstitutional.

His position aligns with his dissenting opinions in earlier Voting Rights Act cases, where he argued that the law was being misused to justify racial engineering rather than to prevent discrimination.In this latest confrontation, Thomas’s words carried the authority of experience. As the only current justice who grew up under Jim Crow segregation, he often invokes his personal journey as evidence that progress cannot be built on perpetual racial classification.

“He is the living embodiment of the American story,” one conservative commentator said.“He rose from poverty, prejudice, and political persecution to sit on the highest court in the land. And he never compromised his principles to get there.”Thomas’s career milestone has become more than a moment of personal reflection; it is a symbolic marker of the Supreme Court’s rightward evolution.

Once an isolated voice of dissent, he now presides over a majority that often echoes his views. Where he was once derided as an ideological outlier, he is now recognized as the intellectual backbone of modern conservatism.

Supporters describe him as America’s “greatest justice,” a man who never bowed to political pressure. “Justice Thomas has lived the most inspiring American life,” Paoletta said. “He is an American hero and our nation’s greatest justice.”Whether or not one agrees with that assessment, it is undeniable that Thomas’s tenure has reshaped the constitutional landscape.His challenge to race-based districting this week was a continuation of the principles that have guided him since 1991 — the belief that liberty cannot coexist with government-imposed racial distinctions.

As he left the courtroom, the symbolism was unmistakable. Thirty-four years after surviving one of the most ferocious confirmation battles in history, Clarence Thomas remains undaunted.His questions still carry the same quiet ferocity that once stunned the Senate chamber — questions rooted in the conviction that the Constitution’s promise of equality must be more than a slogan.

In a political climate still defined by division and identity politics, Thomas’s message stands as both challenge and reminder.“The Constitution is colorblind,” he once wrote. “It neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens.” And on the eve of his thirty-fourth year on the Court, that conviction remains as unshakable as the man himself.